Bobby Hull’s Golden Hockey Career Diminished by His Troubling Dark Side

Once a star player in Chicago who changed goal scoring and how players were paid, Hull, who died Monday at 84, will rightly be remembered more for his misdeeds.

If ever there was an N.H.L. star whose spectacular feats on the ice were diminished by his misdeeds away from it, it was Bobby Hull.

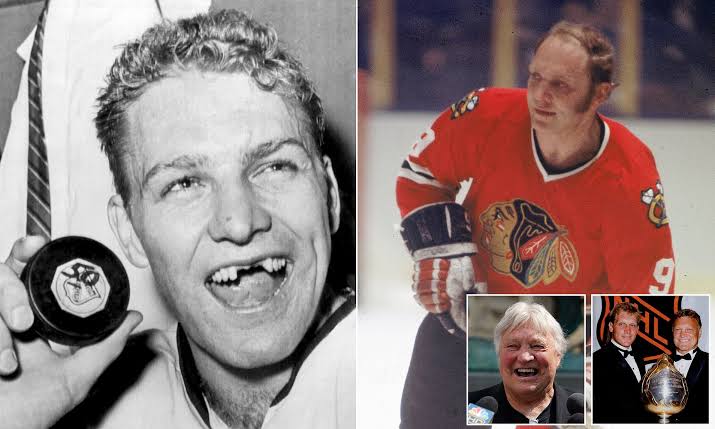

His blond hair and matinee-idol looks combined with the stirring solo rushes up the ice that usually ended in his fearsome slapshot hitting the back of the net brought him the nickname The Golden Jet. But all that hockey gold was tarnished by the darker side of Hull, who died on Monday at the age of 84.

For every accomplishment, like his five 50-goal seasons in 15 years for the Chicago Blackhawks from 1957 to 1972, and all the pioneering steps, like his use of a curved stick or his jump to the upstart World Hockey Association in 1972 that eventually enriched his peers, there were blemishes: credible accusations from two wives of domestic assault; an arrest for assaulting a police officer; and the airing of repugnant views on race, genetics and Hitler.

It will be interesting to see how the N.H.L. and the Blackhawks, the team most associated with Hull, handle memorials for him. The N.H.L. All-Star Game will be played on Saturday in South Florida. The next Chicago home game is Feb. 7. Usually the death of a Hall of Fame star like Hull would merit an emotional tribute at both events, but his conflicting legacy leaves that in doubt.

The N.H.L. has long been criticized for its handling of issues involving sexual assault and racism but has tried to improve its image in recent years. The Blackhawks in particular have earned enormous criticism, especially for the team’s mishandling of a sexual assault accusation in 2010 involving a video coach that resulted in a lawsuit by a former player last year and the departures of several team executives.

So far, neither the league nor the Blackhawks has mentioned any of the problems with Hull’s reputation in acknowledging his death. In an official statement released on Monday, N.H.L. Commissioner Gary Bettman referred to Hull as one of the league’s “most iconic and distinctive players.” Rocky Wirtz, the Blackhawks’ chairman, called Hull “a beloved member of the Blackhawks family.”

A few years after his N.H.L. career began with Chicago in 1957, Hull established himself as the first mainstream superstar in hockey. A muscular farm boy from Point Anne, Ontario, a small cement manufacturing town 120 miles northeast of Toronto, he could bring fans to their feet with his locomotive-like sorties up the ice and was the closest thing to a household name the six-team N.H.L. had as the television age took hold in the 1960s.

Both the league and the Blackhawks quickly recognized the publicity value in Hull. He was the subject of numerous promotions intended to create interest in hockey, especially among women at a time the sport had a mostly male audience. One of the most famous hockey photographs of the 1960s was one of Hull, stripped to the waist, flaxen hair and muscles glistening in the summer sun, tossing hay with a pitchfork on the family farm.